Notes from IASEAI

On agents, ethics, and catastrophic risks

I’ve just come back from the inaugural conference of the International Association for Safe and Ethical AI (IASEAI or “eye-see-eye” apparently… I know).

This is a brief write up of the themes I noticed while I was there. Or really an excuse for me to share some of the thoughts I ended up having at the conference.

2025: The Year of Agents

Everyone was talking about agents. And disagreeing about what an agent is or how big of a deal they are. But everyone agrees that whatever agents are, 2025 is the year of them.

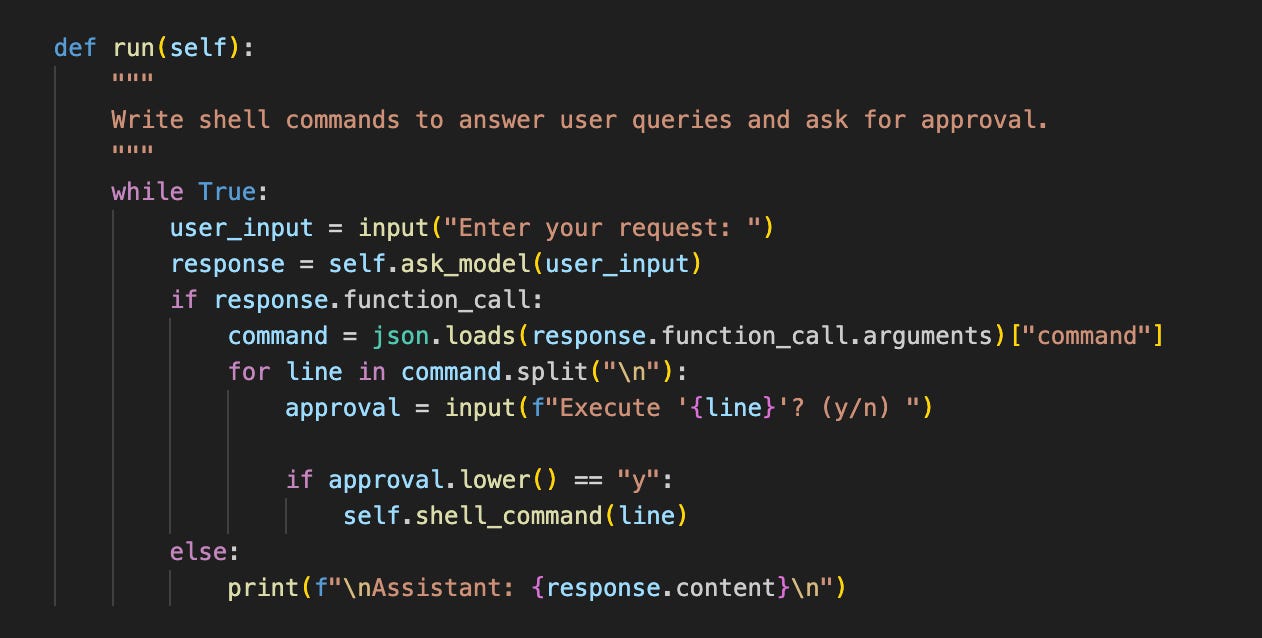

In the context of LLMs, I understand agents to basically be LLMs that can do things.1 The way they can do this is actually elegantly simple. Ordinarily, an LLM runs in a loop: generating likely tokens on the basis of what it’s seen and generated so far. But you can break this loop by watching for special tokens indicating that some other function should be run. For example the LLM might generate “The sum of two and two is <math> 2 + 2 = ?</math>”. And this would trigger a call to a calculator which would return the result into the LLM’s context window: “<result> 4 </result>”

These functions could be simple things like calling a calculator or a database search. Or more complex things like an API call to post on social media or buy a product. Or very open-ended things like executing arbitrary code. New products like Anthropic’s Computer Use and OpenAI’s Operator take this a step further by sending the LLM screenshots of a computer and having it issue mouse and keyboard commands.

Setting up LLMs to take actions is trivially easy. OpenAI have offered ‘function calling’ since June 2023, which allows you to specify a set of functions that models can run. I asked the agent in the example above what the top 10 US baby names were, and it was able to download a relevant dataset and write a bash script to pull them out.

The hard part is getting models to take the right actions in the right way at the right time. Benchmarks like AgentBench, WebShop, and WebArena show that even models which excel at answering questions struggle to do long-horizon planning tasks: handling errors, edge cases, and all the messiness that inevitably comes when you’re interacting with the real world.

This makes a lot of sense in terms of how models have been trained. There are very few examples in models’ training data of the kind of step-by-step planning, debugging, and error-recovery that’s needed to complete real tasks. Most code on the web—in repositories or tutorials—represents the outcome of painstaking planning and debugging, but the errorful process that produced this code is hidden. If you’ve ever tried to follow a tutorial on something you don’t understand well (and run into an error that doesn’t appear in the tutorial), you might have sympathy with this. While it’s easy to copy someone else’s code that works, it takes a much deeper understanding to recover from errors or adapt it to your idiosyncratic use-cases.

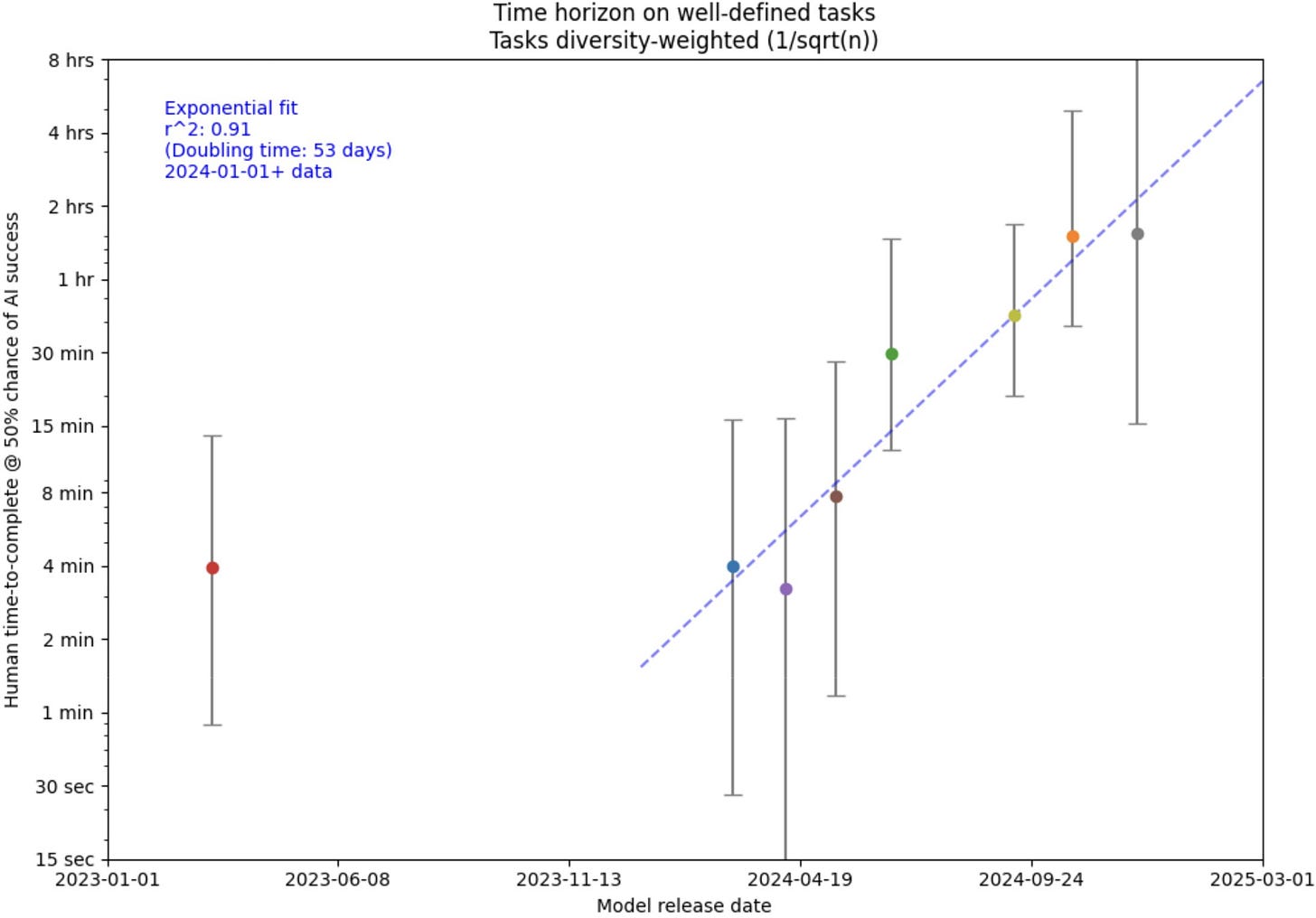

Agents on the rise

But these benchmarks also show that models are improving rapidly at these tasks. The trick has been a combination of training models on these step-by-step, errorful traces of successful problem solving, and using reinforcement learning (RL) to directly reward models for task success. This has led to models like OpenAI’s o1 and DeepSeek’s R1, which learn to generate long “chains of thought” (CoTs) showing their working before answering hard questions. Characteristic of these chains is the “aha moment”, where they will produce tokens like “wait” or “let me check” in the middle of a trace, and explore alternatives to—or potential problems with—what they have generated so far. This tendency could be extremely useful for complex long-term planning.

While writing down your workings might not seem like an especially agentive or impactful action, I actually think that this framing of o1-style models helps to illuminate something profound about what they are doing.

Early LLMs generally processed and generated language as language: as something to be compared to the ground truth of what a human might have said, or something to be shown to a user for approval. These new models are using language to do things: to explore potential solutions, to reconstrue inputs into a format that’s more conducive to solving the problem at hand. These are epistemic actions.

This distinction can be seen most clearly, I think, in DeepSeek-R1-Zero: a model that DeepSeek trained purely using RL, and formed part of the pipeline to creating R1. This model achieved similar accuracy to R1 (solving hard math and coding problems by generating long chains of thought). But the developers decided to train another version, because R1-Zero’s CoTs were impenetrable to human readers. The model would switch languages, use random punctuation tokens, and include apparently unnecessary context. But somehow all this keyboard mashing seemed to help the model.

The model was using to learn language in a very different way to ordinary LLMs—not as a medium to communicate with the user, but as a medium to “think”. This kind of thing is often studied under the heading of steganography—including coded messages in output which are comprehensible to oneself (or potentially a select group of others) but not to a certain target audience. While I think it’s unlikely that this non-human-comprehensibility came about because it was advantageous to the model to hide its reasoning (I think it’s more likely that it was simply more efficient to learn to use language in a new way that was more helpful to the model than to people), it certainly makes me more interested and concerned about what might be contained in reasoning traces of the models we’re using. And I think the general idea of models using language in new ways is fascinating and a great topic for study by cognitive scientists.

Risks from autonomous AI agents

It’s easy to see how this kind of agency and autonomy in a goal-following AI system could be dangerous, along many axes of AI risk. Criminals could use such an agent to persistently trawl important systems for security vulnerabilities and deliberatively create cyber attacks. Autonomous agents also present the greatest systemic risks to employment, as systems which can complete a variety of long-horizon tasks without human intervention could be used to automate many computer-based jobs.

In my own work, I worry a lot about risks from persuasion. A very persuasive agent with access to just a Twitter account could serve the same role as something like an agent-handler for an intelligence agency. They could cross-reference company websites with social media to find vulnerable employees and gain their trust. This kind of relationship could be used for all of the ordinary espionage things (like leaking information in and out of an organisation) but it could also be used for much more dramatic things like persuading powerful figures to change policies or initiate conflicts.

Autonomy makes less of a difference for misuse risks because the users would approve of the agent’s action. Autonomy just allows the agent to pursue nefarious ends with less human activity and expertise. The real difference-making-difference of autonomy comes from misalignment risks: risks around agents acting in a way that their users and developers don’t intend.

First of all, autonomy makes misalignment more likely to go undetected. Current systems would be hard pressed to effect much impact without the approval of their human handlers because they require so much hand-holding. As agents improve, developers will monitor them less (because they’re successful without human-in-the-loop intervention). This creates more space for misalignment (as humans are less involved in the decisions) and more opportunity for it to go unnoticed (especially if people are monitoring models’ behaviour using metrics and reports that models have partial control over).

Second, the way that we train models to be autonomous makes misalignment more likely. Being a persistent, successful “agent” requires planning, following goals in a strategic and deliberate way, and handling unplanned distractions and detours on the way to your goal. One of the first things you might learn if you’re being trained to be such an agent is not to be stopped or turned off. In Stuart Russel’s memorable phrase: “you can’t fetch the coffee if you’re dead.” Another handy maxim might be “acquire power and resources whenever you can, you never know when they might be useful.”

Objectives like self-preservation and resource-acquisition are often referred to as “instrumentally convergent subgoals” because for a wide variety of tasks they end up being instrumentally useful. We might expect that models trained to be excellent at many such tasks will inevitably learn to pursue these goals in the course of them. Note that this doesn’t require models ever being nefarious or “having their own ends”. They’re learning to pursue these things precisely to be as good as possible at doing what we are telling them to do. Nevertheless, if they over-generalise the value of things like self-preservation and power, they might end up with a tendency to pursue these goals overly-well, either when left to their own devices, or in the background while pursuing the goals that we give them.

Finally, autonomy makes the consequences of misalignment much, much worse. It’s not so bad to lose control of an agent that can’t get very far without you. But if it’s an agent that’s good at long-term planning, acquiring resources, keeping itself running securely, and pursuing whatever arbitrary ends it happens to have, this could be a total disaster.

In particular, I think it massively increases total extinction risk. Lots of other natural disasters that might, say, kill 90% of the human population, are very unlikely to kill 100% of it. People are highly adaptable: we’ve survived ice ages, supervolcanoes, and global pandemics. A nuclear winter or climate change might make much of the world uninhabitable, but it will do so in a dispassionate, random way. A nuclear winter won’t dynamically adapt to seek out a ragtag group of survivors hiding out in a bomb shelter. But a misaligned AI agent might.

If such a system ever did acquire a goal like “kill all humans”, it might be capable of pursuing it with ruthless diligence: turning over every last stone and group of uncontacted people until the last one was gone.

It might seem unlikely that machines would ever come to have such a bizarre goal. I’m hoping to write something longer soon on why that might happen. And to be clear I do think this whole scenario is relatively unlikely: not least because we’re still very far away from systems that could survive without any human support. But even if the probability is relatively small, the outcome is potentially so bad that I think it’s worth even over-investing in trying to minimise the chance of this happening.

Intuitions vary around how much worse total human extinction would be than an ordinary catastrophe. I have several friends who think that the death of 90% of the population would be 90% as bad as everyone dying. Personally, I think total extinction would be immeasurably worse. Perhaps chauvinistically, I think it’s neat that human beings can both marvel at the stars and explain what they are. As far as I know we are the only type of system that can do both. Perhaps irrationally, I think it’s worth dedicating a lot of time and energy to ensuring that some of us, at least, keep going.

Agents at IASEAI

Understandably, then, agents, at IASEAI, were widely regarded as a bad move. In fact, several keynote speakers drew agency as a red line which they argued we should not cross. Yoshua Bengio said we ought to be creating AI scientists which can process data but can’t take actions in the world. Max Tegmark said that the real A in AGI should stand for autonomous, and that as long as we didn’t create autonomous generally intelligent systems we might be alright. Margaret Mitchell’s talk (and excellent paper) was simply titled: “Fully Autonomous AI Agents should Not be Developed”).

I’m not sure if I fully agree with this conclusion. Agency and autonomy also promise many of the biggest benefits of AI. However, even to the extent that I do, I’m not sure that these proposals are feasible. Both with respect to defining agents, reaching consensus on preventing agents, and above all on enforcing such a rule.

As I said above, creating theoretically autonomous agents is superficially trivial: just stick them in a loop with a terminal and run the commands they output. Any teenager with a laptop could do this. Today’s models won’t get far in this world, but some of these issues could likely be solved with better software engineering and fine-tuning (which is almost impossible to monitor and regulate).

The really dangerous stuff, however, is probably going to take a significant increase in model capabilities at tasks like creating an AWS account, setting up a server, and running a copy of the model itself (and if you’ve ever wrestled with AWS IAM permissions you will know this is no mean feat). There are levers more levers we could pull to slow down progress there. Improving long horizon planning might take expensive model runs, that are easier to track and regulate. But practically doing this is likely to prove incredibly challenging.

Safe and Ethical

If you’re not particularly familiar with AI research, you might think that building safe AI systems and building ethical AI systems would be broadly commensurate goals, and that people working on these things would largely admire one another’s work. Unfortunately there has in fact been a longstanding rift between these two groups of researchers, somewhere between mutual neglect and mutual disdain.

This isn’t just some Judean People’s Front thing. There are deep ideological differences between these groups. AI Ethics researchers have for years been identifying flagrant ways in which current AI systems exacerbate societal inequality and cause unchecked harm to vulnerable people: from systemic racial biases in sentencing systems, to reinforcing gender stereotypes, and increasing energy demands. Safety researchers, by contrast, are traditionally focussed on more speculative, catastrophic, and long term harms (like the role AI might play in creating chemical weapons, fomenting nuclear war, and ultimately human extinction).

Ethics researchers accuse safetyists of neglecting immediate and concrete harms to real people in order to focus on sci-fi dystopian futures that may never come to pass. Safety researchers accuse ethicists of essentially rearranging deck-chairs on the Titanic.

One happy theme of the IASEAI was an explicit focus on both safety and ethics, and in particular their inseparability. Margaret Mitchell stressed that catastrophic risks are deeply related to contemporary forms of dataset bias. Joseph Stiglitz argued that the near-term risks from AI systems replacing human labour could cause large-scale economic problems. Kate Crawford argued that the rapidly rising energy costs of AI systems present both ethical and safety concerns for all of humanity. And Anca Dragan I think summarized this best by saying that as head of AI Safety and Alignment at Deepmind, she doesn’t have the luxury to choose between safety and ethics: she has to ensure systems benefit everyone, both now and in the future.

I see my own research as sitting at the intersection of ethics and safety research: AI systems can already deceive and manipulate people and these effects are likely to be distributed unevenly toward the most vulnerable. At the same time, I think increases in manipulative capabilities could pose more systemic and catastrophic risks in the future. I rarely feel that there is significant tradeoff between trying to measure and mitigate both of these risks at the same time.

Although the historical tension between safety and ethics researchers is understandable, I’ve always found it slightly frustrating and counterproductive. So it was great to see so many people work toward healing this divide.

Doom and Gloom

Overall though, I found the mood music at the conference pretty sombre.

Importantly, this was a very particular kind of crowd. People who sign up to go to a conference on AI ethics and safety are more likely to be concerned about risks. But even then I was struck by how much consensus there was that we are currently not on a promising path with respect to developing beneficial AI. There was a general feeling that capabilities are advancing much more quickly than many had anticipated (especially on the heels of the R1 and o3 releases). But there was very little consensus on what the right path would look like, and much less how we could get there.

As I said above, many speakers’ proposed solutions were simply not to develop certain types of technology (such as autonomous agents). But they did not address any of the practical regulatory, enforcement, or international cooperation challenges with implementing that kind of strategy. I think that’s fair enough. Max Tegmark and Yoshua Bengio are not policy or international relations experts. If they can convince people that the correct goal is not to develop agents, this is still an important contribution and others with relevant expertise can work on how to make that happen. Personally, I was definitely moved toward more being anti-autonomy over the course of the conference.

In the absence of a more detailed plan, however, I’m sceptical that simply banning certain kinds of AI technology will work. Firstly, because of overwhelming commercial demand for these technologies. Silicon Valley is already teeming with startups promising to create AI assistant which will autonomously undertake the work of an employee. Second, because they’re hard to police. Even the current generation of models could potentially be useful agents with sufficient RL and software engineering, which is relatively cheap and hard to prevent. Third, we’ve already seen reluctance to produce even relatively toothless AI regulation like SB1047. JD Vance’s claim that “The AI future is not going to be won by hand-wringing about safety. It will be won by building” seems a strong signal that US Federal regulation is not about to get any more muscular. Fourth, a lot of the controls (both in terms of alignment and monitoring) rely on models being closed-source. Open-weights models can be deployed without safeguards and fine-tuned to remove any post-training safety behaviour and recent trends suggest that open-weights models are at pace with (or only a few months behind) closed labs like OpenAI. Finally, enforcing any kind of ban or moratorium requires total international cooperation. A single country permitting dangerous models to be trained and deployed could cause international harm.

I’m very in favour of more AI regulation: something along the lines of SB1047 and hopefully more advanced auditing and post-deployment monitoring. But I also think we need to start preparing for a world in which we have powerful autonomous open-source AI systems—at a high-human level on a wide range of skills including software engineering, cybersecurity, writing, persuasion, and planning—in the next 1-3 years. Practically, I think that means more people focussing on things like adaptation, resilience, security, target-side mitigations, and whatever the AI safety equivalent of counterintelligence is.

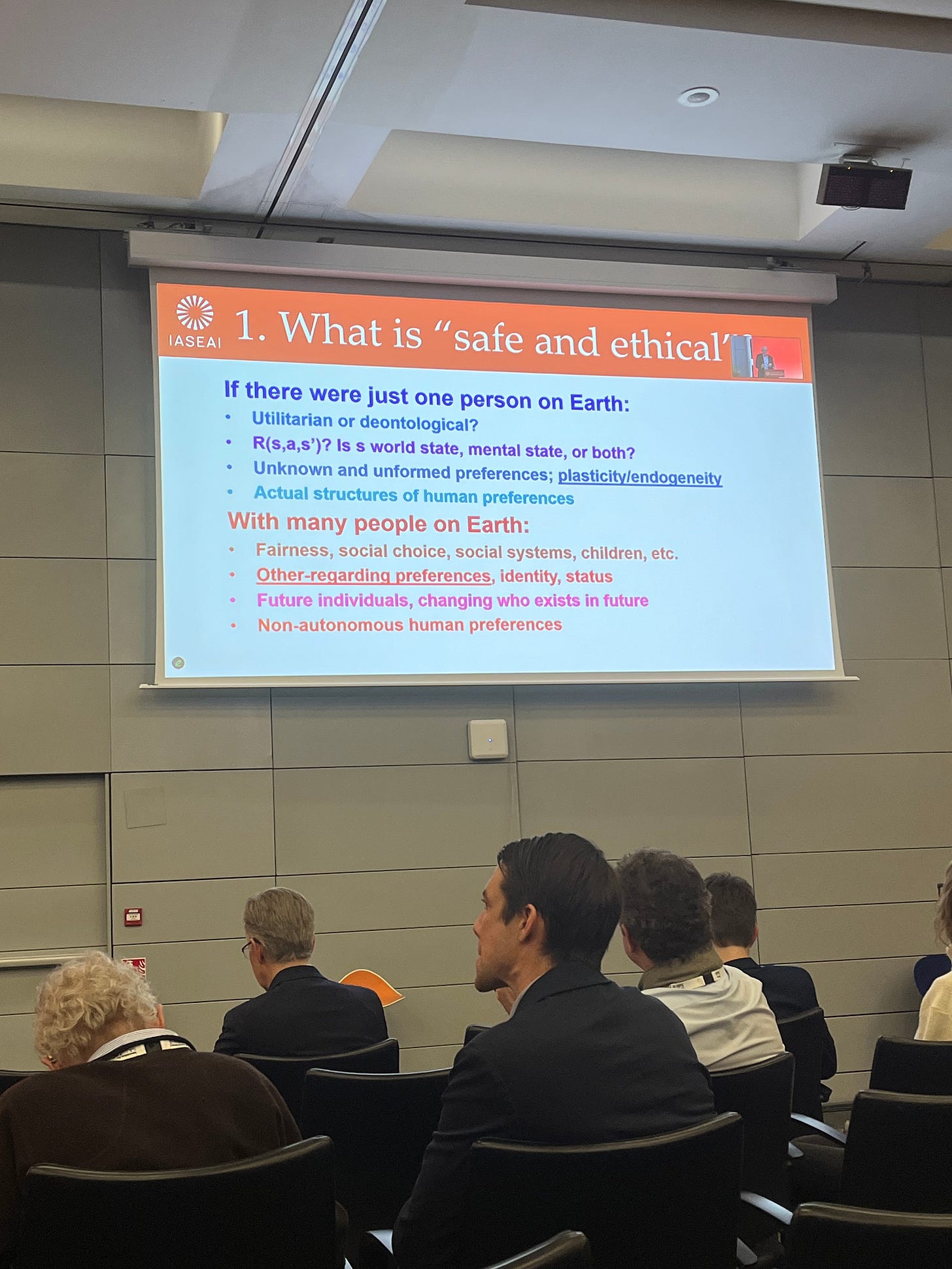

Stuart Russel ended the conference with what I thought was an excellent speech on the challenges of ensuring a safe and ethical future with AI. He listed 5 individual problems that we have to solve: 1) Defining safe and ethical systems; 2) figuring out how to build them; 3) proving that they are safe; 4) requiring that safe and ethical systems be used; and 5) preventing unsafe and unethical systems from operating.

I appreciated that he spent a while on the first challenge: it seems unlikely that people will agree any time soon on what constitutes a safe and ethical system—even in a toy world with just one person. The remaining challenges each seem equally daunting.

Russel motivated his speech with an analogy to aviation safety. We wouldn’t get on a plane without strong assurances that it was safe. He argued that AI was something like a plane that all of humanity was about to board. And not only would we not have a chance to thoroughly test it in advance, but it would have to fly forever: without ever malfunctioning, crashing, or touching the ground. I found this metaphor quite motivating, particularly because we might be taking off in just a couple of years.

I think a lot of confusion is caused by the various different uses of agent (e.g. the relatively inert sense of agent to mean an entity that can take actions in the world, reinforcement learning agents that sense an environment and pursue goals, and deeper philosophical notions of agency that place requirements on the independence and provenance of goal-following behaviour). I can’t address that (interesting & important!) discussion here. So I’ve tried to use a very minimal definition of agent that I think gives you goal-following behaviour for free (a good agent has to pursue goals to act well). I don’t think deeper senses of agency are important for any of the argument here. As Max Tegmark put it in his talk: ‘to a pilot being pursued by a heat-seeking missile, the fact that the missile lacks goals in a deeper sense is of little comfort’.